Book Appointment Now

Advancing Neurorehabilitation: Virtual Reality in Physical Therapy for Neurological Recovery

Introduction

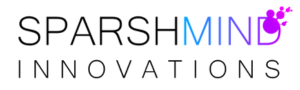

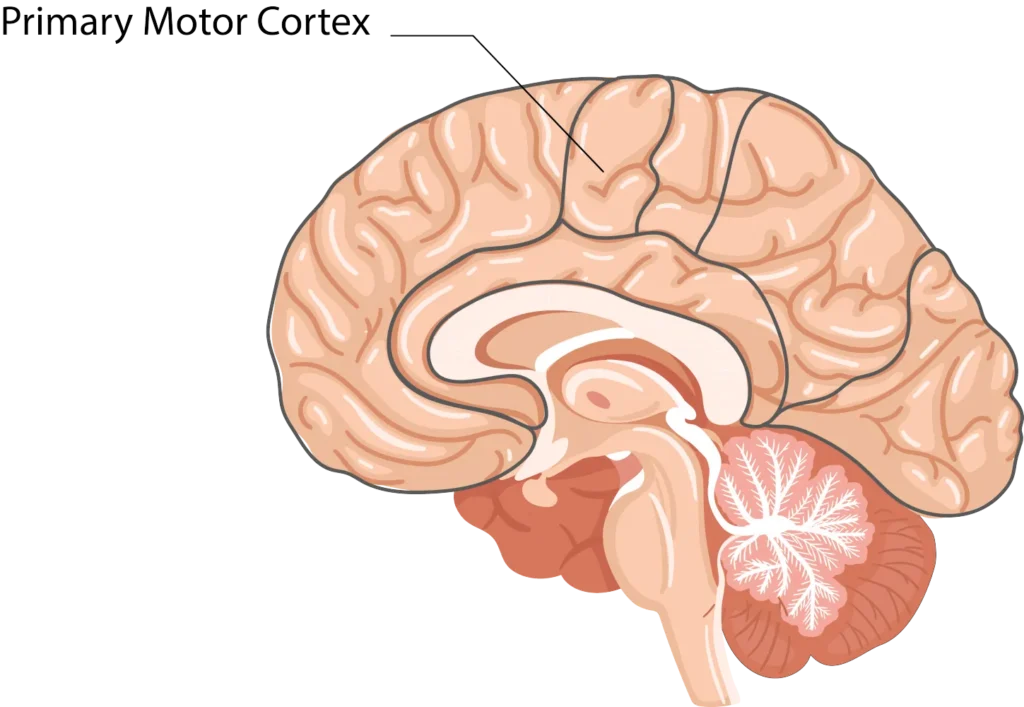

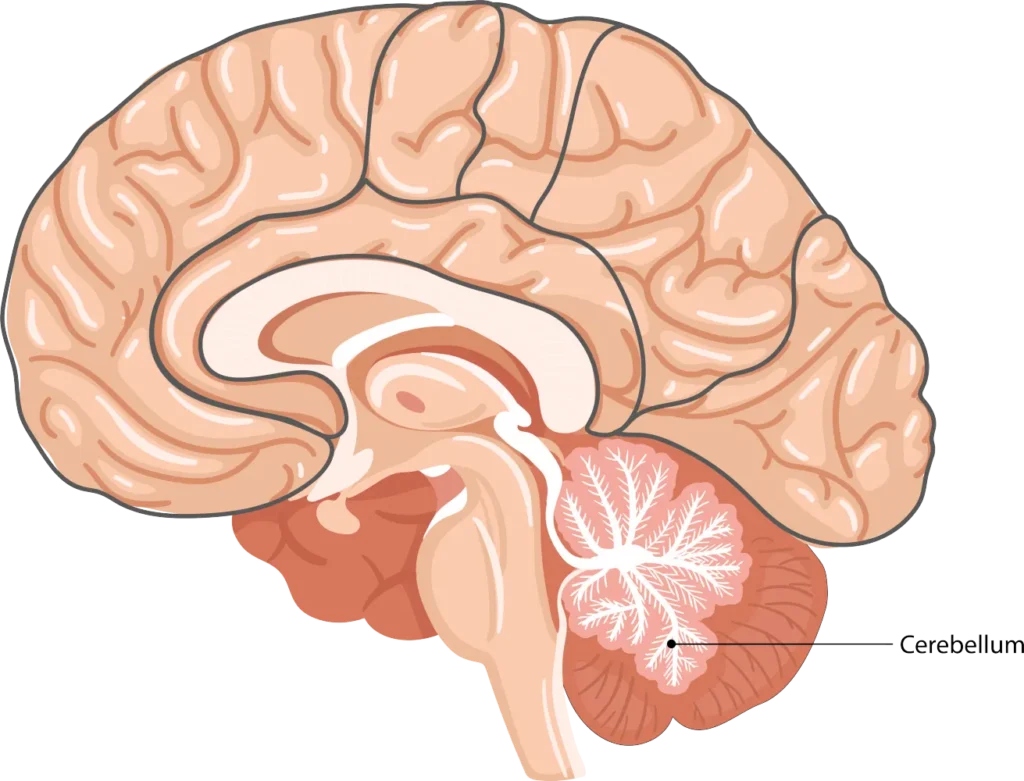

The integration of virtual reality (VR) technology with physiotherapy is revolutionizing rehabilitation protocols for patients with neurological conditions [1,2]. This convergence effectively addresses the intricate interplay between motor function, neuroplasticity, and physical recovery by targeting key neural structures such as the motor cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia [3,4]. Through immersive, task-specific interventions, VR fosters motor relearning, enhances sensory feedback, and strengthens weakened neural circuits, offering a compelling solution for individuals recovering from stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), spinal cord injury (SCI), and movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease [5].

Neuroanatomical Basis of VR-Enhanced Physiotherapy

The therapeutic efficacy of VR in physiotherapy is grounded in its capacity to engage multiple neural pathways simultaneously. By integrating real-time feedback, controlled task progression, and multisensory stimulation, VR augments the neural mechanisms responsible for movement coordination, balance, and postural control [1,6]. Key neuroanatomical regions targeted through VR interventions include:

Primary Motor Cortex (M1)Primary Motor Cortex (M1)

- Location and Role: M1, in the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe, plays a central role in voluntary motor control. After neurological injury, reorganization of M1 is critical for regaining lost motor abilities [4].

- Repetitive Motor Task Execution: Goal-oriented VR exercises, with high-intensity repetition, stimulate M1 plasticity, strengthening corticospinal pathways [1,7].

- Mirror Therapy Principles: VR environments can simulate limb movement in a controlled setting, activating mirror neuron systems—particularly relevant in stroke rehabilitation [2,8].

- Bilateral Coordination Training: Immersive exercises that require synchronous movement of both limbs can enhance interhemispheric communication when one hemisphere is impaired.

Cerebellum

- Balance and Coordination: The cerebellum refines motor activity to ensure smooth, accurate movements. Damage often results in ataxia, loss of fine motor control, and postural instability [5].

- Dynamic Balance Training: Virtual environments challenge postural stability by simulating various terrains, requiring real-time postural adjustments that reinforce cerebellar function [6,9].

- Adaptive Motor Learning: VR tasks can progressively increase in complexity, promoting error-based learning and neuroadaptive plasticity in cerebellar circuits [7].

- Vestibulocerebellar Stimulation: Through immersive head-tracking and visual perturbations, VR enhances the integration of vestibular and proprioceptive inputs, improving overall postural equilibrium [9].

Basal Ganglia

- Movement Initiation and Automaticity: The basal ganglia (caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, substantia nigra) regulate movement initiation, sequencing, and motor automatization [3].

- Structured Movement Sequencing: Step-by-step, guided VR tasks enhance procedural motor learning, a crucial aspect of restoring automatic motor control.

- Dopaminergic Pathway Activation: Reward-based feedback systems within VR can promote dopamine release, reinforcing correct motor execution [8].

- Motor Automatization: High-frequency, repetitive VR training facilitates the shift from conscious motor planning to automatic execution, reducing reliance on cortical compensation strategies [10].

VR technology augments traditional physiotherapy by introducing adaptive, data-driven rehabilitation techniques. The key mechanisms through which VR facilitates neural recovery include:

Proprioceptive Training

- Haptic Feedback Systems: Wearable sensors and force-feedback devices provide real-time proprioceptive cues, reinforcing accurate limb positioning [11].

- Visual–Motor Integration: By synchronizing on-screen movement with motor execution, VR improves sensorimotor integration in the somatosensory cortex [12].

- Error-Based Learning: Immediate feedback allows patients to self-correct movement errors in-session, strengthening compensatory pathways in the parietal cortex [7,9].

Motor Learning and Neural Plasticity

- Task-Oriented Therapy: Gamified VR exercises encourage goal-directed motor activity, promoting synaptic strengthening in sensorimotor networks [1,13].

- Bimanual Coordination Enhancement: Bilateral training modules in VR engage both hemispheres, reinforcing interhemispheric connectivity [2].

- Neurofeedback Modulation: Real-time neurofeedback trains patients to optimize motor output by actively engaging cortical motor circuits [2,14].

Balance and Postural Control

- Vestibular Rehabilitation: VR-based balance exercises stimulate vestibulocerebellar and vestibulospinal pathways, essential for maintaining postural stability [9,15].

- Dual-Task Training: Combining cognitive and motor tasks in a virtual environment enhances postural control under complex conditions, reducing fall risk [6,16].

- Reactive Balance Challenges: By simulating external perturbations, VR prepares patients for real-life balance disruptions, strengthening compensatory mechanisms [5,7].

Conclusion

VR technology represents a groundbreaking advancement in neurorehabilitation, offering a personalized, data-driven approach to physiotherapy. By precisely targeting neural circuits underlying motor control, balance, and proprioception, VR-enhanced physiotherapy fosters superior functional recovery in patients with neurological conditions [1–3,15]. Ongoing research continues to refine VR methodologies, optimizing therapeutic outcomes through more immersive hardware, motion-tracking systems, and adaptive algorithms [2,17].

For physiotherapists and rehabilitation specialists seeking to integrate VR into clinical practice, professional consultation is available to discuss evidence-based protocols, patient-specific customization, and long-term rehabilitation strategies [1,5,18].

Data-Driven Virtual Reality Science

Contemporary Virtual Reality Science incorporates advanced analytics and monitoring capabilities. These systems collect and analyze detailed performance metrics in real-time, enabling therapists to make informed decisions about treatment progression. The data-driven approach allows for precise tracking of patient progress, facilitating the development of highly personalized rehabilitation programs.

References

- Laver KE, Lange B, George S, et al. Virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(11):CD008349.

- Howard MC. A meta-analysis and systematic literature review of virtual reality rehabilitation programs. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;70:317–327.

- McEwen D, Polatajko H, Davis J, Huijbregts M. “There’s a real plan here, and I am responsible for that plan”: Participant experiences with a novel blended approach to stroke rehabilitation involving virtual reality and task-specific training. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;7(1):e14808.

- Saposnik G, Levin M. Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: A meta-analysis and implications for clinicians. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1380–1386.

- Crosbie JH, Lennon S, Basford JR, McDonough SM. Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: Still more virtual than real. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(14):1139–1146.

- Mirelman A, et al. Noninvasive brain stimulation and virtual reality—an emerging technology for improving gait and reducing falls in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2021;36(4):889–903.

- Holden MK. Virtual environments for motor rehabilitation: review. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8(3):187–211.

- Cano Porras D, Siemonsma P, Inzelberg R, Hermens H, Klarenbeek B. Advantages of virtual reality in the rehabilitation of balance and gait: Systematic review. Neurology. 2019;94(23):1017.

- Saposnik G, et al. Stroke outcomes research Canada working group. Stroke. 2010;41(8):1724–1731.

- Calabrò RS, Naro A, De Luca R, et al. Shaping neuroplasticity by using powered exoskeletons in patients with stroke: A randomized clinical trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2018;15(1):35.

- Olmos LE, Collado-Vázquez S, Rodríguez-Hernández M, et al. Wearable and portable sensor technologies for stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. Sensors (Basel). 2018;18(7):2157.

- Alashram AR, Annino G, Padua E. Cognitive motor interference during walking after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(11):2743–2755.

- Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, Prevo AJ. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: Impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2181–2186.

- Barth JT, Freeman JR, Broshek DK, Varney RN. Accentuating the positive: Cognitive-behavioral rehabilitation of frontal lobe deficits. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(1):39–51.

- Yang Y, Bi S, Zhao Q, et al. Effect of VR-based balance training on postural control in stroke patients: A meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2020;79:174–180.

- Foley MP, Bhatt T, Redfern MS. Dual-task postural stability: Current trends and future directions for Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;46(1):55–66.

- De Biase S, Cook L, Skelton DA, et al. The COVID-19 rehabilitation pandemic. Age Ageing. 2020;49(5):696–700.

- Proffitt R, Lange B. User centered design and development of a game for exercise in stroke. Games Health J. 2015;4(6):359–364.